By Karen Remo-Listana

Wednesday, December 31, 2008

www.business24-7.ae

The dollar is set to head higher in the first half of next year, before giving back some of its gains in the second half, assuming the global economy bottoms next summer, a report from Morgan Stanley said.

"As the world cycles through summer, fall, winter and spring, investors can anticipate various cyclical currency trades. US dollar strengthens as the world slows, but will weaken as the world recovers," said the report, sent to Emirates Business. And since the world is likely to enter deeper into the "winter" season, the dollar should strengthen further. But when "spring' comes, the dollar is likely to give back some of its gains.

"In 2009, assuming that the global economy does find a trough by summer, we see the dollar rallying further into the trough, but underperforming most other currencies as the world recovers in the second half," it said.

Through its "Four Seasons'" currency concept, the New York-based investment bank said real global economic growth and equity buoyancy demarcate four distinct scenarios for the world, further noting that different currencies tend to perform best in these four quadrants.

The US Treasuries will likely remain well supported while a flare-up in inflation is not a probable risk, the report added.

There are two main risks however to Morgan Stanley's dollar view – inflation and an unsustainable federal debt profile.

The Fed's QE operations, it said, need an exit strategy. The latest talk of the Fed issuing its own debt may be one way the Fed could unwind its balance sheet in time to stabilise inflation expectations.(Bennie Bucks to the rescue? - AM) In addition, the dollar's performance will be driven by inflation expectations.

Similarly, the super-sized US fiscal deficits will be a risk for the dollar, though it views the US Treasuries are more likely to be a preferred safe haven asset in a global recession, marginalizing other sovereign debt.

On the other hand, Morgan Stanley says emerging market (EM) currencies are 'summer' currencies that do not perform well in 'winter' while euro – historically a "winter" currency – will suffer because of possible fractures in Eastern Europe.

"EM currency 'moment' is not over, in our view," it said. "In fact, the process is roughly halfway complete. We see weaker Latam currencies in the first half. Pressures on AXJ currencies will likely persist, as these countries' exports collapse and their central banks cut interest rates. We believe that even the Chinese yuan will be allowed to weaken against the dollar in the coming months."

It said Eastern European currencies may come under intense balance of payments pressures while the situation in Russia especially deserves investors' full attention, as "the familiar structural fragilities of Eastern Europe will expose the broad region to possible discrete changes in the rouble" it said.

It remains bearish on the euro in the first half. "Though the euro is no longer over-valued, it is still over-rated and over-owned," it said.

"We would not be surprised if the world's reserve holdings of British pound and Swiss franc start to decline from here, with the euro being a beneficiary of this prospective new trend," Morgan Stanley said.

Tuesday, December 30, 2008

Capitalism matches mankind

(Another favorite of mine from Winnie: The inherent vice of capitalism is the unequal sharing of blessings; the inherent virtue of socialism is the equal sharing of miseries. - AM)

Commentary by Caroline Baum

Dec. 30 (Bloomberg)

The year 2008 will be remembered as one that exposed the fatal flaws in free-market capitalism, sending it to an untimely death.

Or will it?

That capitalism’s obituary is already being written suggests the enemies of the free market were waiting to pounce.

Last week, Arianna Huffington, co-founder of the Huffington Post, wrote that laissez-faire capitalism, “a monumental failure in practice,” should be “as dead as Soviet Communism” as an ideology.

On National Public Radio, Daniel Schorr pronounced “the death of a doctrine” in his year-end review.

All I could think of was Winston Churchill’s assertion about democracy. Capitalism is surely the worst economic system, except for all the others that have been tried.

With its ideology under fire and its practice falsely maligned, it is to the defense of free markets that I devote my final column of the year.

Before you can declare free markets a failure, you have to establish that they exist, says Paul Kasriel, chief economist at the Northern Trust Co. in Chicago.

“We do not have free markets in credit in the U.S. or anywhere else that I know of,” he says. “The price of short- term credit is fixed by central banks. It would only be by accident that a central bank would fix the price of short-term credit” at the precise level that a free market would.

Fixing the price of any other commodity, including labor, has proven to be a failure, an affront to the inviolable invisible hand. Yet when it comes to setting the interest rate that will keep the economy on an even keel, we put our faith in a chosen few to get it right.

All sorts of unintended consequences flow forth from central bankers’ fixing of a short-term rate. Hold the rate too low, and it leads to a misallocation of capital into, say, housing or dot- com stocks. That’s what happened in the late 1990s and again in the early part of this decade.

“We are now experiencing the economic and financial market fallout from (Alan) Greenspan’s interference with the free market,” Kasriel says.

In a true free market, risk-takers are punished for bad bets. Not so in the current crisis, where financial institutions -- with the exception of Lehman Brothers -- are deemed too big to fail and rescued, merged or recapitalized.

One supposed nail in capitalism’s coffin is the assertion that deregulation created the problems. This is curious, given that banks, which are at the root of the credit crunch, are among the most highly regulated institutions.

“There is a small army of people overseeing the banking industry,” says Paul DeRosa, a partner at Mt. Lucas Management Corp. in New York. And yet “we’ve had a banking crisis every 15 years since 1837. The number of people devoted to regulation doesn’t seem to matter.”

Regulators from the Federal Reserve, Securities and Exchange Commission, Office of the Controller of the Currency and New York State Banking Commission are “on the premises 365 days a year,” he says.

The regulatory structure may have been antiquated and overlapping. That’s no excuse for the regulators to be caught napping.

Censuring the free market is a way of deflecting blame from the true source, according to Dan Mitchell, senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute in Washington.

“The genesis of the problem is bad government policy,” Mitchell says, pointing to everything from easy money to “affordable lending schemes” to the “corrupt system of subsidies from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac” to the tax code’s favorable treatment of debt (the interest is deductible) versus equity.

Fannie’s and Freddie’s generous campaign contributions (anywhere else, these would be called bribes) encouraged Congress to look the other way as the two housing finance agencies used their implicit government guarantee to increase their leverage and buy riskier mortgages.

Those clamoring for more regulation as a solution to the current crisis are forgetting that Congress has oversight responsibility for the regulator of those agencies.

“I have no confidence regulation will solve the problem,” says Allan Meltzer, professor of economics at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. “Lawyers and bureaucrats make regulations. Markets figure out how to circumvent the costly ones.”

As a case in point, Meltzer pointed to the Basel Accords, which “required banks that hold more risky assets to hold more reserves. So they held them off their balance sheet, where they went from being poorly monitored to not monitored at all.”

Capitalism has spread across the globe, lifting millions out of poverty as “a direct consequence of government stepping out of the way,” DeRosa says.

Yet critics of free-market capitalism are implicitly arguing for a bigger role for government.

Alas, government isn’t some benevolent matriarch acting in the public interest, even if it knew what that was. It is a conglomeration of politicians acting in their own self-interest, guided by payoffs from special-interest groups. That’s a poor substitute for the market’s price signals, not to mention a guarantee of inefficiency and waste.

“Capitalism is the only system that produces both growth and freedom,” Meltzer says. Unlike socialism and communism, “it doesn’t depend on someone’s ideas of perfection.”

Yes, markets are guilty of excess, greed, even corruption.

“We’re not perfect people,” Meltzer says. “Capitalism matches mankind."

Commentary by Caroline Baum

Dec. 30 (Bloomberg)

The year 2008 will be remembered as one that exposed the fatal flaws in free-market capitalism, sending it to an untimely death.

Or will it?

That capitalism’s obituary is already being written suggests the enemies of the free market were waiting to pounce.

Last week, Arianna Huffington, co-founder of the Huffington Post, wrote that laissez-faire capitalism, “a monumental failure in practice,” should be “as dead as Soviet Communism” as an ideology.

On National Public Radio, Daniel Schorr pronounced “the death of a doctrine” in his year-end review.

All I could think of was Winston Churchill’s assertion about democracy. Capitalism is surely the worst economic system, except for all the others that have been tried.

With its ideology under fire and its practice falsely maligned, it is to the defense of free markets that I devote my final column of the year.

Before you can declare free markets a failure, you have to establish that they exist, says Paul Kasriel, chief economist at the Northern Trust Co. in Chicago.

“We do not have free markets in credit in the U.S. or anywhere else that I know of,” he says. “The price of short- term credit is fixed by central banks. It would only be by accident that a central bank would fix the price of short-term credit” at the precise level that a free market would.

Fixing the price of any other commodity, including labor, has proven to be a failure, an affront to the inviolable invisible hand. Yet when it comes to setting the interest rate that will keep the economy on an even keel, we put our faith in a chosen few to get it right.

All sorts of unintended consequences flow forth from central bankers’ fixing of a short-term rate. Hold the rate too low, and it leads to a misallocation of capital into, say, housing or dot- com stocks. That’s what happened in the late 1990s and again in the early part of this decade.

“We are now experiencing the economic and financial market fallout from (Alan) Greenspan’s interference with the free market,” Kasriel says.

In a true free market, risk-takers are punished for bad bets. Not so in the current crisis, where financial institutions -- with the exception of Lehman Brothers -- are deemed too big to fail and rescued, merged or recapitalized.

One supposed nail in capitalism’s coffin is the assertion that deregulation created the problems. This is curious, given that banks, which are at the root of the credit crunch, are among the most highly regulated institutions.

“There is a small army of people overseeing the banking industry,” says Paul DeRosa, a partner at Mt. Lucas Management Corp. in New York. And yet “we’ve had a banking crisis every 15 years since 1837. The number of people devoted to regulation doesn’t seem to matter.”

Regulators from the Federal Reserve, Securities and Exchange Commission, Office of the Controller of the Currency and New York State Banking Commission are “on the premises 365 days a year,” he says.

The regulatory structure may have been antiquated and overlapping. That’s no excuse for the regulators to be caught napping.

Censuring the free market is a way of deflecting blame from the true source, according to Dan Mitchell, senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute in Washington.

“The genesis of the problem is bad government policy,” Mitchell says, pointing to everything from easy money to “affordable lending schemes” to the “corrupt system of subsidies from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac” to the tax code’s favorable treatment of debt (the interest is deductible) versus equity.

Fannie’s and Freddie’s generous campaign contributions (anywhere else, these would be called bribes) encouraged Congress to look the other way as the two housing finance agencies used their implicit government guarantee to increase their leverage and buy riskier mortgages.

Those clamoring for more regulation as a solution to the current crisis are forgetting that Congress has oversight responsibility for the regulator of those agencies.

“I have no confidence regulation will solve the problem,” says Allan Meltzer, professor of economics at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. “Lawyers and bureaucrats make regulations. Markets figure out how to circumvent the costly ones.”

As a case in point, Meltzer pointed to the Basel Accords, which “required banks that hold more risky assets to hold more reserves. So they held them off their balance sheet, where they went from being poorly monitored to not monitored at all.”

Capitalism has spread across the globe, lifting millions out of poverty as “a direct consequence of government stepping out of the way,” DeRosa says.

Yet critics of free-market capitalism are implicitly arguing for a bigger role for government.

Alas, government isn’t some benevolent matriarch acting in the public interest, even if it knew what that was. It is a conglomeration of politicians acting in their own self-interest, guided by payoffs from special-interest groups. That’s a poor substitute for the market’s price signals, not to mention a guarantee of inefficiency and waste.

“Capitalism is the only system that produces both growth and freedom,” Meltzer says. Unlike socialism and communism, “it doesn’t depend on someone’s ideas of perfection.”

Yes, markets are guilty of excess, greed, even corruption.

“We’re not perfect people,” Meltzer says. “Capitalism matches mankind."

This thing of ours

Federal Reserve Press Release

Release Date: December 30, 2008

For immediate release

The Federal Reserve on Tuesday announced that it expects to begin operations in early January under the previously announced program to purchase mortgage-backed securities (MBS) (half a trillion worth - AM) and that it has selected private investment managers to act as its agents in implementing the program.

Because of the size and complexity of the agency MBS program, a competitive request for proposal (RFP) process was employed to select four investment managers and a custodian. The investment managers are BlackRock Inc., Goldman Sachs Asset Management, PIMCO and Wellington Management Company, LLP.

(Wasn't sure why Wellington was named ... but now I do, they are the 3rd largest institutional holder of GS stock. Welcome to the 'waste management business'. -AM)

GOLDMAN SACHS

TOP INSTITUTIONAL HOLDERS

Holder / Shares / % Out / Value / Reported

Barclays Global Investors UK Holdings Ltd 17,355,918 4.39 $2,221,557,504 30-Sep-08

STATE STREET CORPORATION 16,769,356 4.24 $2,146,477,568 30-Sep-08

WELLINGTON MANAGEMENT COMPANY, LLP 15,840,670 4.01 $2,027,605,760 30-Sep-08

Release Date: December 30, 2008

For immediate release

The Federal Reserve on Tuesday announced that it expects to begin operations in early January under the previously announced program to purchase mortgage-backed securities (MBS) (half a trillion worth - AM) and that it has selected private investment managers to act as its agents in implementing the program.

Because of the size and complexity of the agency MBS program, a competitive request for proposal (RFP) process was employed to select four investment managers and a custodian. The investment managers are BlackRock Inc., Goldman Sachs Asset Management, PIMCO and Wellington Management Company, LLP.

(Wasn't sure why Wellington was named ... but now I do, they are the 3rd largest institutional holder of GS stock. Welcome to the 'waste management business'. -AM)

GOLDMAN SACHS

TOP INSTITUTIONAL HOLDERS

Holder / Shares / % Out / Value / Reported

Barclays Global Investors UK Holdings Ltd 17,355,918 4.39 $2,221,557,504 30-Sep-08

STATE STREET CORPORATION 16,769,356 4.24 $2,146,477,568 30-Sep-08

WELLINGTON MANAGEMENT COMPANY, LLP 15,840,670 4.01 $2,027,605,760 30-Sep-08

SEC digs deep

(That all you got Cox? - AM)

By David Scheer

Dec. 30 (Bloomberg

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, under congressional scrutiny for failing to detect Bernard Madoff’s alleged $50 billion Ponzi scheme, said it halted an unrelated $23 million scam targeting Haitian-Americans.

A federal judge in Miami agreed to freeze assets and appoint a receiver after the SEC sued George Theodule and two companies he helped control, claiming he lured investors by promising to double their money within 90 days, the agency said in a statement today. Theodule lost at least $18 million on securities trades in the past year, while early investors got funds raised from later participants, the SEC said.

Theodule, 48, encouraged people to form investment clubs that funneled funds to the firms, raising more than $23 million since November 2007, the SEC said. Participants were told some profits would fund ventures benefiting the Haitian community in the U.S., Haiti and Sierra Leone, it said.

“This alleged Ponzi scheme preyed upon unsuspecting members of a close-knit community, attempting to take advantage of the trust they had in each other,” Linda Thomsen, the SEC’s enforcement director, said in the agency’s statement.

By David Scheer

Dec. 30 (Bloomberg

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, under congressional scrutiny for failing to detect Bernard Madoff’s alleged $50 billion Ponzi scheme, said it halted an unrelated $23 million scam targeting Haitian-Americans.

A federal judge in Miami agreed to freeze assets and appoint a receiver after the SEC sued George Theodule and two companies he helped control, claiming he lured investors by promising to double their money within 90 days, the agency said in a statement today. Theodule lost at least $18 million on securities trades in the past year, while early investors got funds raised from later participants, the SEC said.

Theodule, 48, encouraged people to form investment clubs that funneled funds to the firms, raising more than $23 million since November 2007, the SEC said. Participants were told some profits would fund ventures benefiting the Haitian community in the U.S., Haiti and Sierra Leone, it said.

“This alleged Ponzi scheme preyed upon unsuspecting members of a close-knit community, attempting to take advantage of the trust they had in each other,” Linda Thomsen, the SEC’s enforcement director, said in the agency’s statement.

Holy C.R.A.P. Pimpco!

By DAMIAN PALETTA and JOHN D. STOLL

Wall Street Journal

December 30, 2008

WASHINGTON -- The federal government Monday deepened its involvement in the U.S. automotive industry by committing $6 billion to stabilize GMAC LLC, a financing company vital to the future of struggling car maker General Motors Corp.

In a sign the government's role in the industry could become open-ended, the Treasury Department said Monday it had set up a separate program within the Troubled Asset Relief Program (Can I be the first? Car Rescue Asset Program, C.R.A.P.- AM), a fund originally designed to help banks, to make investments directed at the auto industry. A Treasury official said the new program didn't have a specific dollar limit.(Wherever our imagination takes us?-AM)

The Treasury purchased $5 billion in senior preferred equity in GMAC and offered a new $1 billion loan to GM so the auto maker could participate in a rights offering at GMAC. (Oh this is the priceless part. PIMPCO not only doesn't take a loss, not only gets the juice from GMAC debt ramping cause your taxpayer money is subordinate but gets the Government to pony up 1 billion so that GMAC can hit the 75% limit. Will Paul McCulley's next blogging adventure with Bun Bun,his Netherlands Dwarf pet bunny,-hand to God check out their web site - be entitled, 'Yo, we punk'd the taxpayer?' -AM) That loan comes in addition to the recent $17.4 billion emergency plan to rescue GM and Chrysler LLC.

The move by Treasury is the second part of a two-step rescue by the government of GMAC.(Part 2 of 2? Isn't that optimistic? -AM) Last week, the Federal Reserve approved the finance company's application to become a bank-holding company, a move sought by other companies, too, to take advantage of new government programs aimed at stabilizing banks.

The Fed's approval was conditional on GMAC raising new capital, which the company tried to do through a debt-equity swap that expired Friday. The company's goal was to raise $30 billion by converting 75% of its issued debt into preferred-stock holdings. Last week, less than 60% of bondholders had signed on and the offering had been extended four times. At the same time as the Treasury announcement Monday, GMAC said it had raised enough capital to satisfy the Fed's conditions. It wasn't clear whether the government's intervention prompted or followed GMAC's meeting the capital requirement.(Read your full article, I guess when it's written by committee -4 folks cited - they don't check each other's notes - AM)

—Neal Boudette and Sharon Terlep contributed to this article.

Wall Street Journal

December 30, 2008

WASHINGTON -- The federal government Monday deepened its involvement in the U.S. automotive industry by committing $6 billion to stabilize GMAC LLC, a financing company vital to the future of struggling car maker General Motors Corp.

In a sign the government's role in the industry could become open-ended, the Treasury Department said Monday it had set up a separate program within the Troubled Asset Relief Program (Can I be the first? Car Rescue Asset Program, C.R.A.P.- AM), a fund originally designed to help banks, to make investments directed at the auto industry. A Treasury official said the new program didn't have a specific dollar limit.(Wherever our imagination takes us?-AM)

The Treasury purchased $5 billion in senior preferred equity in GMAC and offered a new $1 billion loan to GM so the auto maker could participate in a rights offering at GMAC. (Oh this is the priceless part. PIMPCO not only doesn't take a loss, not only gets the juice from GMAC debt ramping cause your taxpayer money is subordinate but gets the Government to pony up 1 billion so that GMAC can hit the 75% limit. Will Paul McCulley's next blogging adventure with Bun Bun,his Netherlands Dwarf pet bunny,-hand to God check out their web site - be entitled, 'Yo, we punk'd the taxpayer?' -AM) That loan comes in addition to the recent $17.4 billion emergency plan to rescue GM and Chrysler LLC.

The move by Treasury is the second part of a two-step rescue by the government of GMAC.(Part 2 of 2? Isn't that optimistic? -AM) Last week, the Federal Reserve approved the finance company's application to become a bank-holding company, a move sought by other companies, too, to take advantage of new government programs aimed at stabilizing banks.

The Fed's approval was conditional on GMAC raising new capital, which the company tried to do through a debt-equity swap that expired Friday. The company's goal was to raise $30 billion by converting 75% of its issued debt into preferred-stock holdings. Last week, less than 60% of bondholders had signed on and the offering had been extended four times. At the same time as the Treasury announcement Monday, GMAC said it had raised enough capital to satisfy the Fed's conditions. It wasn't clear whether the government's intervention prompted or followed GMAC's meeting the capital requirement.(Read your full article, I guess when it's written by committee -4 folks cited - they don't check each other's notes - AM)

—Neal Boudette and Sharon Terlep contributed to this article.

Monday, December 29, 2008

Yuan Watch : 2012 Unification?

By Ko Shu-ling

Tuesday, Dec 30, 2008

Taipei Times

Beijing is likely to expedite the process of unification with Taiwan and possibly try to achieve the goal by 2012, an expert attending a cross-strait forum said yesterday.

Lai I-chung, an executive member of the pro-localization Taiwan Thinktank and former director of the Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) International Affairs Department, said that 2012 is a year important to Taiwan’s survival.

As Chinese President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao are scheduled to step down, they are likely to do something to leave a historic legacy and set the course for their successors, Lai said.

Also, President Ma Ying-jeou’s four-year term will expire and Beijing is likely to make an effort to help Ma win the election. If Ma loses, Beijing would speed up its unification efforts, Lai said.

Washington is preoccupied with financial and other domestic problems, Japan is suffering from political instability and India has switched its concerns to internal problems, so the US is likely to pay little attention to the Taiwan Strait as long as it obtains Beijing’s assurance that its interests in the region were not under threat, Lai added.

If Beijing’s economy continues to deteriorate, its leaders are likely to adopt drastic measures to divert public attention, Lai said. Possible scenarios include creating conflict or even launching a military assault under the pretext of a crackdown on an uprising in the wake of Ma’s election defeat.

Lai made the remarks during a forum organized by the Institute for National Development in Taipei yesterday morning. The forum was held to analyze the just concluded economic forum between the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Lai said Taiwan was facing an “immediate and present danger,” the prelude of a historic tragedy, such as the 1938 annexation of Austria into Greater Germany by the Nazis.

The impact of such a possibility in 2012 far outweighs the repercussion of the KMT-CCP forum, Lai said.

Soochow University political science professor Lo Chih-cheng said that Ma’s China policy had pushed the nation toward unprecedented peril and that Beijing’s Taiwan strategy was to lay the groundwork for de jure unification with Taiwan.

Among the problems Taiwan faces, Lo said, was Beijing and Taipei’s teaming up to “internalize” cross-strait relations. Second, the KMT-CCP economic forums are moving toward setting the agenda for cross-strait negotiations.

Taipei is cooperating with Beijing to exclude international invention in the Taiwan Strait and make the Taiwan question China’s internal affair, Lo said. As the Ma administration thinks the shortcut to the international community is through Beijing, it has pinned all the nation’s hopes of participation in international organizations on Beijing’s goodwill.

“Taiwan must learn a lesson from Hong Kong,” Lo said. “If no one in Taiwan or the international community can rein in the Ma administration’s determination to unify with China, Taiwan will be doomed because we are entering a danger zone.”

Tuesday, Dec 30, 2008

Taipei Times

Beijing is likely to expedite the process of unification with Taiwan and possibly try to achieve the goal by 2012, an expert attending a cross-strait forum said yesterday.

Lai I-chung, an executive member of the pro-localization Taiwan Thinktank and former director of the Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) International Affairs Department, said that 2012 is a year important to Taiwan’s survival.

As Chinese President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao are scheduled to step down, they are likely to do something to leave a historic legacy and set the course for their successors, Lai said.

Also, President Ma Ying-jeou’s four-year term will expire and Beijing is likely to make an effort to help Ma win the election. If Ma loses, Beijing would speed up its unification efforts, Lai said.

Washington is preoccupied with financial and other domestic problems, Japan is suffering from political instability and India has switched its concerns to internal problems, so the US is likely to pay little attention to the Taiwan Strait as long as it obtains Beijing’s assurance that its interests in the region were not under threat, Lai added.

If Beijing’s economy continues to deteriorate, its leaders are likely to adopt drastic measures to divert public attention, Lai said. Possible scenarios include creating conflict or even launching a military assault under the pretext of a crackdown on an uprising in the wake of Ma’s election defeat.

Lai made the remarks during a forum organized by the Institute for National Development in Taipei yesterday morning. The forum was held to analyze the just concluded economic forum between the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Lai said Taiwan was facing an “immediate and present danger,” the prelude of a historic tragedy, such as the 1938 annexation of Austria into Greater Germany by the Nazis.

The impact of such a possibility in 2012 far outweighs the repercussion of the KMT-CCP forum, Lai said.

Soochow University political science professor Lo Chih-cheng said that Ma’s China policy had pushed the nation toward unprecedented peril and that Beijing’s Taiwan strategy was to lay the groundwork for de jure unification with Taiwan.

Among the problems Taiwan faces, Lo said, was Beijing and Taipei’s teaming up to “internalize” cross-strait relations. Second, the KMT-CCP economic forums are moving toward setting the agenda for cross-strait negotiations.

Taipei is cooperating with Beijing to exclude international invention in the Taiwan Strait and make the Taiwan question China’s internal affair, Lo said. As the Ma administration thinks the shortcut to the international community is through Beijing, it has pinned all the nation’s hopes of participation in international organizations on Beijing’s goodwill.

“Taiwan must learn a lesson from Hong Kong,” Lo said. “If no one in Taiwan or the international community can rein in the Ma administration’s determination to unify with China, Taiwan will be doomed because we are entering a danger zone.”

Yuan Watch : Fraud prevention

(I know that you know what I'm thinkin' - AM)

straitstimes.com

December 29, 2008

BEIJING - An executive at a major Chinese state-owned mining company was sentenced to death for taking bribes and embezzling more than US$10 million (S$14.4 million), state media reported on Monday.

Yu Weiping, deputy manager of Yunnan Copper Group, took bribes of more than 4 million dollars, and embezzled over 41 million yuan (S$8.6 million), the official Xinhua news agency reported.

Yu also misappropriated 27 million yuan and lent the money to others, Xinhua quoted the Intermediate People's Court in Kunming, capital of the southwestern province of Yunnan, as saying.

straitstimes.com

December 29, 2008

BEIJING - An executive at a major Chinese state-owned mining company was sentenced to death for taking bribes and embezzling more than US$10 million (S$14.4 million), state media reported on Monday.

Yu Weiping, deputy manager of Yunnan Copper Group, took bribes of more than 4 million dollars, and embezzled over 41 million yuan (S$8.6 million), the official Xinhua news agency reported.

Yu also misappropriated 27 million yuan and lent the money to others, Xinhua quoted the Intermediate People's Court in Kunming, capital of the southwestern province of Yunnan, as saying.

Crazy is as crazy forecasts

By Tony Jackson

December 29th, 2008

Financial Times

Absolute Strategy Research (ASR) calculates that for Europe, the ratio of buys to hold/sell recommendations hit about 63 per cent at the start of 2008, just after the market's all-time peak. The trough of 38 per cent came back in 2003, just as the market was poised for an explosive four-year rally. The ratio is now a little over 50 per cent, suggesting the market has further to fall. (One need not be sociopathic to be a stock 'analyst' but obviously neither is it detrimental to the cause - AM)

Back in the real world, my guess is that equities will not be the real story next year, any more than they were in this. That is not to say equity markets will be calm. Rather, they will be an expression of what is happening elsewhere, mainly in credit.

Begin with the fact that corporate defaults are still eerily low. According to Standard & Poor's, the latest 12-month trailing figure for global defaults was 2.7 per cent. This compares with the average for 1981-2007 - that is, excluding the period of almost zero defaults at the peak of the bubble - of 4.4 per cent.

Even leveraged loans - mainly a legacy of the private equity bubble - were on a default rate of only 3.8 per cent, compared with a peak in 2002 of almost 6 per cent.

But the distress rate - the proportion of loans trading below 80 cents on the dollar - is off the scale at 76 per cent, compared with a 2002 peak of just 10 per cent. If that figure is half-way right, watch out.

Ditto with the behaviour of banks' loan officers. According to the US Federal Reserve, 84 per cent of US banks are now restricting lending to large corporates. That compares with about 60 per cent in the past two recessions.

December 29th, 2008

Financial Times

Absolute Strategy Research (ASR) calculates that for Europe, the ratio of buys to hold/sell recommendations hit about 63 per cent at the start of 2008, just after the market's all-time peak. The trough of 38 per cent came back in 2003, just as the market was poised for an explosive four-year rally. The ratio is now a little over 50 per cent, suggesting the market has further to fall. (One need not be sociopathic to be a stock 'analyst' but obviously neither is it detrimental to the cause - AM)

Back in the real world, my guess is that equities will not be the real story next year, any more than they were in this. That is not to say equity markets will be calm. Rather, they will be an expression of what is happening elsewhere, mainly in credit.

Begin with the fact that corporate defaults are still eerily low. According to Standard & Poor's, the latest 12-month trailing figure for global defaults was 2.7 per cent. This compares with the average for 1981-2007 - that is, excluding the period of almost zero defaults at the peak of the bubble - of 4.4 per cent.

Even leveraged loans - mainly a legacy of the private equity bubble - were on a default rate of only 3.8 per cent, compared with a peak in 2002 of almost 6 per cent.

But the distress rate - the proportion of loans trading below 80 cents on the dollar - is off the scale at 76 per cent, compared with a 2002 peak of just 10 per cent. If that figure is half-way right, watch out.

Ditto with the behaviour of banks' loan officers. According to the US Federal Reserve, 84 per cent of US banks are now restricting lending to large corporates. That compares with about 60 per cent in the past two recessions.

Mr. Steel meets hottest fire

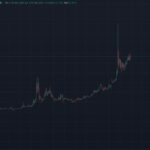

(An accompanying graph to this article shows that steel industry output closely tracks global GDP output -watching steel prices can be a good indication of larger trends. Steel is also a good proxy for China which is the world's biggest steel producing and consuming nation. China has contributed more to global growth than any other country in this recent expansion. The steel ETF, SLX, has been absolutely crushed in the last 6 months falling 73%. Despite its' climb from November lows, it has fallen ~15% again in the last 10 days - AM)

By Peter Marsh

Published: December 29 2008 02:00

Financial Times

Global steel production could easily plunge by 10 per cent or more next year, with China leading the slump in output.

But although the industry is in its worst state since steel prices hit rock bottom towards the end of 2001, some industry observers believe there are a few bright spots on the horizon.

"The speed and decisiveness of the cutbacks in production [by big steelmakers] have been unprecedented, which means profitability in this downturn for the steel industry is likely to hold up better than in other comparable periods," says John Lichtenstein, head of the metals industry group at Accenture.

By controlling supply better than in previous downturns, steel companies should be in a better position to keep prices at fairly high levels - and so guard against too steep a fall in earnings, he believes.

Backing up this argument is research from Meps, a UK-based steel consultancy, which expects average prices of all steel grades sold worldwide to climb marginally over the next few months, rather than continue the steep falls that started in July.

According to Meps, average steel prices should rise to $750 a tonne by next July, from a low point of $676 a tonne seen earlier this month.

Even though the price has fallen precipitously from $1,160 a tonne in July 2008, today's steel price is still considerably above the low point of $275 a tonne seen in November 2001, which was the last time the sector was in a state of slump.

Rod Beddows, chief executive of Hatch Corporate Finance, a financial group specialising in the metals industry, reckons the steel business should be bracing itself for a "sharp" downturn "with a period of four years between the sector returning to the level of output and demand it experienced in the first half of 2008".

Matthias Hellstern, who monitors the European steel industry on behalf of Moody's, says that any upturn that comes later in 2009, perhaps around the second or third quarters, will be "extremely mild".

Mr Hellstern reckons there is a chance that global steel production will fail to return to the levels of the first half of 2008 until 2013.

On the assumption that steel production in 2008 will be slightly lower than the 1.34bn tonnes recorded in 2007, it could, according to Mr Hellstern's calculations, be more than five years before annual output sector climbs again to this level.

According to data from the London-based Iron and Steel Statistics Bureau, an industry research body, there have been only four occasions since 1900, apart from periods of world wars, when the global steel sector has taken four years or longer to climb out of a downturn by attaining the previous high point in production.

However, not all analysts are quite as downbeat as Mr Hellstern.

Peter Marcus, managing partner at World Steel Dynamics, a US consultancy, believes that output could rebound by 12.9 per cent in 2010, following a fall of 13.9 per cent in 2009, which would mean annual output returning to the level of 2007 in 2011.

By Peter Marsh

Published: December 29 2008 02:00

Financial Times

Global steel production could easily plunge by 10 per cent or more next year, with China leading the slump in output.

But although the industry is in its worst state since steel prices hit rock bottom towards the end of 2001, some industry observers believe there are a few bright spots on the horizon.

"The speed and decisiveness of the cutbacks in production [by big steelmakers] have been unprecedented, which means profitability in this downturn for the steel industry is likely to hold up better than in other comparable periods," says John Lichtenstein, head of the metals industry group at Accenture.

By controlling supply better than in previous downturns, steel companies should be in a better position to keep prices at fairly high levels - and so guard against too steep a fall in earnings, he believes.

Backing up this argument is research from Meps, a UK-based steel consultancy, which expects average prices of all steel grades sold worldwide to climb marginally over the next few months, rather than continue the steep falls that started in July.

According to Meps, average steel prices should rise to $750 a tonne by next July, from a low point of $676 a tonne seen earlier this month.

Even though the price has fallen precipitously from $1,160 a tonne in July 2008, today's steel price is still considerably above the low point of $275 a tonne seen in November 2001, which was the last time the sector was in a state of slump.

Rod Beddows, chief executive of Hatch Corporate Finance, a financial group specialising in the metals industry, reckons the steel business should be bracing itself for a "sharp" downturn "with a period of four years between the sector returning to the level of output and demand it experienced in the first half of 2008".

Matthias Hellstern, who monitors the European steel industry on behalf of Moody's, says that any upturn that comes later in 2009, perhaps around the second or third quarters, will be "extremely mild".

Mr Hellstern reckons there is a chance that global steel production will fail to return to the levels of the first half of 2008 until 2013.

On the assumption that steel production in 2008 will be slightly lower than the 1.34bn tonnes recorded in 2007, it could, according to Mr Hellstern's calculations, be more than five years before annual output sector climbs again to this level.

According to data from the London-based Iron and Steel Statistics Bureau, an industry research body, there have been only four occasions since 1900, apart from periods of world wars, when the global steel sector has taken four years or longer to climb out of a downturn by attaining the previous high point in production.

However, not all analysts are quite as downbeat as Mr Hellstern.

Peter Marcus, managing partner at World Steel Dynamics, a US consultancy, believes that output could rebound by 12.9 per cent in 2010, following a fall of 13.9 per cent in 2009, which would mean annual output returning to the level of 2007 in 2011.

Sunday, December 28, 2008

Yuan Watch : Lock-up Expiration

By Winny Wang | 2008-12-29

ShanghaiDaily.com

Share investors are advised to be cautious in the last three days of trading for this year as concerns persist over possible selling of non-tradable equities in the Shanghai stock market, analysts said.

The lock-up periods of 13.2 billion non-tradable shares, accounting for 2.6 percent of the circulation in the A-share market, expire over the last 10 days of this month.

"A total of 650 million non-tradable shares have been sold so far this month, equivalent to 4.81 billion yuan and a rise of 73.85 percent from a month earlier, which greatly dampened the market's performance," said Zhou Yu, an analyst at Pacific Securities Co.

"Concerns over declining corporate earnings and a resumption of new share sales will be under the spotlight in the early part of next year," said Teng Yin, an analyst of Everbright Securities Co.

Liu Xinhua, assistant chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission, last week said the regulator will encourage pension funds, insurers and mutual funds to invest more in the domestic stock markets.

ShanghaiDaily.com

Share investors are advised to be cautious in the last three days of trading for this year as concerns persist over possible selling of non-tradable equities in the Shanghai stock market, analysts said.

The lock-up periods of 13.2 billion non-tradable shares, accounting for 2.6 percent of the circulation in the A-share market, expire over the last 10 days of this month.

"A total of 650 million non-tradable shares have been sold so far this month, equivalent to 4.81 billion yuan and a rise of 73.85 percent from a month earlier, which greatly dampened the market's performance," said Zhou Yu, an analyst at Pacific Securities Co.

"Concerns over declining corporate earnings and a resumption of new share sales will be under the spotlight in the early part of next year," said Teng Yin, an analyst of Everbright Securities Co.

Liu Xinhua, assistant chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission, last week said the regulator will encourage pension funds, insurers and mutual funds to invest more in the domestic stock markets.

A taste without excessive vig

By Samantha Zee

Dec. 28 (Bloomberg)

IndyMac Bank is close to being sold to a group of private equity and hedge fund firms in a transaction that may be announced as early as tomorrow, the New York Times reported, citing unidentified people briefed on the matter.

The buyers include private equity firms J.C. Flowers & Co.(led by ex-Goldie J. Christopher Flowers) and Dune Capital Management (founded by ex-Goldie Daniel Niedich and Steven Mnuchin) and the hedge fund firm Paulson & Co. (mortgage vulture extraordinaire), the people told the newspaper. The proposed sale is unusual in that it’s one of the first transactions involving unregulated private equity firms acquiring a bank-holding company, the Times said in its Dealbook section.

The investor group would buy the whole California-based mortgage lender that was seized by U.S. regulators five months ago. The purchase would include IndyMac’s 33 branches, reverse- mortgage unit and its $176 billion loan-servicing portfolio, the newspaper said.

(Oh and by the way below is the plan Bair proposed right around the time Timmy G let it be leaked he wanted her out because she was more concerned about the FDIC then the financial system as a whole. Hmmm... sure will be interesting what the Three Amigos propose as an alternative won't it? - AM)

'Under the plan, people who took out fixed-rate mortgages from IndyMac Federal would be able to seek lower priced loans if they were in, or near, default. The FDIC authorized IndyMac to modify loans that were 60 days or more delinquent, allowing monthly payments to be reduced to a level no greater than 38% of monthly household income.'- CEP News December 4, 2008

Dec. 28 (Bloomberg)

IndyMac Bank is close to being sold to a group of private equity and hedge fund firms in a transaction that may be announced as early as tomorrow, the New York Times reported, citing unidentified people briefed on the matter.

The buyers include private equity firms J.C. Flowers & Co.(led by ex-Goldie J. Christopher Flowers) and Dune Capital Management (founded by ex-Goldie Daniel Niedich and Steven Mnuchin) and the hedge fund firm Paulson & Co. (mortgage vulture extraordinaire), the people told the newspaper. The proposed sale is unusual in that it’s one of the first transactions involving unregulated private equity firms acquiring a bank-holding company, the Times said in its Dealbook section.

The investor group would buy the whole California-based mortgage lender that was seized by U.S. regulators five months ago. The purchase would include IndyMac’s 33 branches, reverse- mortgage unit and its $176 billion loan-servicing portfolio, the newspaper said.

(Oh and by the way below is the plan Bair proposed right around the time Timmy G let it be leaked he wanted her out because she was more concerned about the FDIC then the financial system as a whole. Hmmm... sure will be interesting what the Three Amigos propose as an alternative won't it? - AM)

'Under the plan, people who took out fixed-rate mortgages from IndyMac Federal would be able to seek lower priced loans if they were in, or near, default. The FDIC authorized IndyMac to modify loans that were 60 days or more delinquent, allowing monthly payments to be reduced to a level no greater than 38% of monthly household income.'- CEP News December 4, 2008

Yuan Watch : Petitioning the Big Red Dragon

By SHEN HONG and DENIS MCMAHON

December 27th, 2008

Wall Street Journal

SHANGHAI -- A group of foreign banks in China has asked the Chinese government to delay a recently imposed tax on interest paid on money borrowed from overseas, arguing that the tax would exacerbate the impact of the global financial crisis.

The request concerns a new withholding tax on interest payments on all loans to banks in China from overseas lenders. The tax, which is retroactive to Jan. 1, is expected to disproportionately affect the Chinese operations of foreign banks, which are more likely to borrow from overseas sources, such as their parent companies. Chinese banks typically have large deposit bases, so are less reliant on borrowing from overseas.

A petition signed by 36 foreign banks, seen Friday by Dow Jones Newswires, describes the tax as an excessive burden on foreign lenders operating in China. The petition was signed Dec. 23 and addressed to China's State Council, its banking regulator, its central bank and the Ministry of Finance.

The new tax is technically directed at the offshore lenders, saying they must pay tax on the interest they earn on loans made to banks in China.

However, the China-based entity is responsible for paying the tax on the lender's behalf, the statement said.

Under China's corporate income-tax regulations, a 10% withholding tax will be broadly charged, but a lower rate of 7% will be placed on lenders from places with which China has a tax treaty, such as Hong Kong.

A cover letter for the petition from accounting firm Ernst & Young said the measure, together with recent changes to the banks' business tax, could roughly add an additional 1 billion yuan ($146.2 million) to the banking sector's tax bill this year.

"As far as an independent bank is concerned, this could be the difference between surviving the financial crisis or not," the accounting firm said in the letter addressed to the tax bureau.

December 27th, 2008

Wall Street Journal

SHANGHAI -- A group of foreign banks in China has asked the Chinese government to delay a recently imposed tax on interest paid on money borrowed from overseas, arguing that the tax would exacerbate the impact of the global financial crisis.

The request concerns a new withholding tax on interest payments on all loans to banks in China from overseas lenders. The tax, which is retroactive to Jan. 1, is expected to disproportionately affect the Chinese operations of foreign banks, which are more likely to borrow from overseas sources, such as their parent companies. Chinese banks typically have large deposit bases, so are less reliant on borrowing from overseas.

A petition signed by 36 foreign banks, seen Friday by Dow Jones Newswires, describes the tax as an excessive burden on foreign lenders operating in China. The petition was signed Dec. 23 and addressed to China's State Council, its banking regulator, its central bank and the Ministry of Finance.

The new tax is technically directed at the offshore lenders, saying they must pay tax on the interest they earn on loans made to banks in China.

However, the China-based entity is responsible for paying the tax on the lender's behalf, the statement said.

Under China's corporate income-tax regulations, a 10% withholding tax will be broadly charged, but a lower rate of 7% will be placed on lenders from places with which China has a tax treaty, such as Hong Kong.

A cover letter for the petition from accounting firm Ernst & Young said the measure, together with recent changes to the banks' business tax, could roughly add an additional 1 billion yuan ($146.2 million) to the banking sector's tax bill this year.

"As far as an independent bank is concerned, this could be the difference between surviving the financial crisis or not," the accounting firm said in the letter addressed to the tax bureau.

Auld Lang Syne 2009, Hooray 2010!

( A great prognostication, although I doubt Hilary will put on a veil. - AM)

Chronicle of a decline foretold

By Niall Ferguson

Published: December 27 2008 02:00 | Last updated: December 27 2008 02:00

Financial Times

It was the year when people finally gave up trying to predict the year ahead. It was the year when every forecast had to be revised - usually downwards - at least three times.

The Great Repression began in August 2007 and reached its nadir in 2009. It was clearly not a Great Depression on the scale of the 1930s, when output in the US declined by as much as a third and unemployment reached 25 per cent. Nor was it merely a Big Recession. As output in the developed world continued to decline throughout 2009 - despite the best efforts of central banks and finance ministries - the tag "Great Repression" seemed more and more apt: though this was the worst economic crisis in 70 years, many people remained in deep denial about it.

"We assumed that we economists had learnt how to combat this kind of crisis," admitted one of President Barack Obama's "dream team" of economic advisers, shortly after his return to academic life in September 2009. "We thought that if the Fed injected enough liquidity into the financial system, we could avoid deflation. We thought if the government ran a big enough deficit, we could end a recession. It turned out we were wrong."

The root of the problem remained the US's property bubble, which continued to deflate. Many people had assumed that by the end of 2008 the worst must be over. It was not. House prices continued to slide in the US. As they did, more and more families found themselves in negative equity, with debts exceeding the value of their homes. In turn, rising foreclosures translated into bigger losses on mortgage-backed securities and yet more red ink on banks' balance sheets.

With total debt above 350 per cent of US gross domestic product, the excesses of the age of leverage proved difficult to purge. Households reined in their consumption. Banks sought to restrict new lending. The recession deepened. Unemployment rose towards 10 per cent, and then higher. The economic downward spiral seemed unstoppable. No matter how hard they saved, Americans simply could not stabilise the ratio of their debts to their disposable incomes. The paradox of thrift meant that rising savings translated into falling consumer demand, which led to rising unemployment, falling incomes and so on, ever downwards.

"Necessity will be the mother of invention," Obama declared in his inaugural address on January 20. "By investing in innovation, we can restore our faith in American creativity. We need to build new schools, not new shopping malls. We need to produce clean energy, not dirty derivatives." The rhetoric flew high. But the markets sank lower. The contagion spread inexorably from subprime to prime mortgages, to commercial real estate, to corporate bonds and back to the financial sector. By the end of June, Standard & Poor's 500 Index had sunk to 624, its lowest monthly close since January 1996.

The crux of the problem was the fundamental insolvency of the big banks, another reality that policymakers sought to repress. In 2008, the Bank of England had estimated total losses on toxic assets at about $2.8 trillion. Yet total bank writedowns by the end of 2008 were little more than $583bn, while total capital raised was just $435bn. Losses, in other words, were either being massively understated, or they had been incurred outside the banking system. Either way, the system of credit creation had broken down. The banks could not contract their balance sheets because of a host of pre-arranged credit lines, which their clients were now desperately drawing on, while their only source of new capital was the US Treasury, which had to contend with an increasingly sceptical Congress.

There was uproar when Timothy Geithner, US Treasury secretary, requested an additional $300bn to provide further equity injections for Citigroup, Bank of America and the seven other big banks, just a week after imposing an agonising "mega-merger" on the automobile industry. In Detroit, the Big Three had become just a Big One. The banks, by contrast, seemed to enjoy an infinite claim on public funds. Yet no amount of money seemed enough to persuade them to make new loans at lower rates. As one indignant Michigan lawmaker put it: "Nobody wants to face the fact that these institutions [the banks] are bust. Not only have they lost all of their capital. If we genuinely marked their assets to market, they would have lost it twice over. The Big Three were never so badly managed as these bankrupt banks."

In the first quarter, the Fed continued to do everything in its power to avert the slide into deflation. The effective federal funds rate had already hit zero by the end of 2008. In all but name, quantitative easing had begun in November 2008, with large-scale purchases of the debt and mortgage-backed securities of government-sponsored agencies (the renationalised mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) and the promise of future purchases of government bonds. Yet the expansion of the monetary base was negated by the contraction of broader monetary measures such as M2 (the measurement of money and its "close substitutes", such as savings deposits, that is a key indicator of inflation). The ailing banks were eating liquidity almost as fast as the Fed could create it. The Fed increasingly resembled a government-owned hedge fund, leveraged at more than 75 to 1, its balance sheet composed of assets everyone else wanted to be rid of.

The position of the US federal government was scarcely better. By the end of 2008, the total value of loans, investments and guarantees given by the Fed and the Treasury since the start of the crisis had already reached $7.8 trillion. In the year to November 30 2008, the total federal debt had increased by more than $1.5 trillion. Morgan Stanley estimated that the total federal deficit for the fiscal year 2009 could equal 12.5 per cent of GDP. The figure would have been even higher had Obama not been persuaded by his chief economic adviser, Lawrence Summers, to postpone his planned healthcare reform and promised spending increases in education, research and foreign aid.

Despite the fears of the still-influential former Treasury secretary Robert Rubin, investors around the world were more than happy to buy new issues of US Treasuries, no matter how voluminous. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the quadrupling of the deficit did not lead to falling bond prices and rising yields. Instead, the flight to quality and the deflationary pressures unleashed by the crisis around the world drove long-term yields downwards. They remained at close to 3 per cent all year.

Nor was there a dollar rout, as many had feared. The foreign appetite for the US currency withstood the Fed's money-printing antics, and the trade weighted exchange rate actually appreciated during 2009.

Here was the irony at the heart of the crisis. In all kinds of ways, the Great Repression had "Made in America" stamped all over it. Yet its effects were more severe in the rest of the world than in the US. And, as a consequence, the US managed to retain its "safe haven" status. The worse things got elsewhere, the more readily investors bought Treasuries and held dollars.

For the rest of the world, 2009 proved to be an annus horribilis . Japan was plunged back into the deflationary nightmare of the 1990s by yen appreciation and a collapse of consumer confidence. Things were little better in Europe. By the first quarter of 2009, it became apparent that the problems of the European banks were just as serious as those of their American counterparts. Moreover, in the absence of a European-wide finance ministry, all talk of a European stimulus package was just that - mere talk. In practice, fiscal policy became a matter of sauve qui peut , with each European country improvising its own bailout and its own stimulus package. The result was a mess.

Political instability struck China, where riots by newly redundant workers in Shenzhen and other export centres provoked a heavy-handed clampdown by the government, but also a renewed effort by the People's Bank of China to prevent the appreciation of the yuan by buying up yet more hundreds of billions of dollars of US Treasuries. "Chimerica" - the symbiotic relationship between China and America - not only survived the crisis but gained from it. Although Obama's decision to attend the first G2 summit in Beijing in April dismayed some liberals, most recognised that trade trumped Tibet at such a time of economic crisis.

This asymmetric character of the global crisis - the fact that the shocks were even bigger on the periphery than at the epicentre - had its disadvantages for the US, to be sure. Any hope that America could depreciate its way out from under its external debt burden faded as 10-year yields and the dollar held firm. Nor did American manufacturers get a second wind from reviving exports, as they would have done had the dollar sagged. The Fed's achievement was to keep inflation in positive territory - just. Those who had feared galloping inflation and the end of the dollar as a reserve currency were confounded.

On the other hand, the troubles of the rest of the world meant that in relative terms the US gained, politically as well as economically. Many commentators had warned in 2008 that the financial crisis would be the final nail in the coffin of America's credibility around the world. First, neoconservatism had been discredited in Iraq. Now the "Washington consensus" on free markets had collapsed. Yet this was to overlook two things. The first was that most other economic systems fared even worse than America's when the crisis struck: the country's fiercest critics - Russia, Venezuela - fell flattest. The second was the enormous boost to America's international reputation that followed Obama's inauguration.

If proof were needed that the US constitution still worked, here it was. If proof were needed that America had expunged its original sin of racial discrimination, here it was. And if proof were needed that Americans were pragmatists, not ideologues, here it was. It was not that Obama's New New Deal produced an economic miracle. It was more that the federal takeover of the big banks and the conversion of all private mortgage debt into new 50-year Obamabonds signalled an impressive boldness on the part of the new president.

The same was true of Obama's decision to fly to Tehran in June - a decision that did more than anything else to sour relations with Hillary Clinton, whose supporters never quite recovered from the sight of the former presidential candidate shrouded in a veil. Like Richard Nixon's visit to China in 1972, it symbolised a readiness on Obama's part to rethink the very fundamentals of American grand strategy. And the downfall of the Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad - followed soon after by the abandonment of the country's nuclear weapons programme - was a significant prize in its own right. With their economy prostrate, the pragmatists in Tehran were finally ready to make their peace with "the Great Satan" in return for desperately needed investment.

Meanwhile, al-Qaeda's bungled attempt to assassinate Obama only served to discredit radical Islamism and to reinforce Obama's public image as "The One".

By year end, it was possible for the first time to detect - rather than just to hope for - the beginning of the end of the Great Repression. The downward spiral in America's real estate market and the banking system had finally been halted by radical steps that the administration had initially hesitated to take. At the same time, the far larger economic problems in the rest of the world had given Obama a unique opportunity to reassert American leadership.

The "unipolar moment" was over, no question. But power is a relative concept, as the president pointed out in his last press conference of the year: "They warned us that America was doomed to decline. And we certainly all got poorer this year. But they forgot that if everyone else declined even further, then America would still be out in front. After all, in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king."

And, with a wink, President Barack Obama wished the world a happy new year.

Chronicle of a decline foretold

By Niall Ferguson

Published: December 27 2008 02:00 | Last updated: December 27 2008 02:00

Financial Times

It was the year when people finally gave up trying to predict the year ahead. It was the year when every forecast had to be revised - usually downwards - at least three times.

The Great Repression began in August 2007 and reached its nadir in 2009. It was clearly not a Great Depression on the scale of the 1930s, when output in the US declined by as much as a third and unemployment reached 25 per cent. Nor was it merely a Big Recession. As output in the developed world continued to decline throughout 2009 - despite the best efforts of central banks and finance ministries - the tag "Great Repression" seemed more and more apt: though this was the worst economic crisis in 70 years, many people remained in deep denial about it.

"We assumed that we economists had learnt how to combat this kind of crisis," admitted one of President Barack Obama's "dream team" of economic advisers, shortly after his return to academic life in September 2009. "We thought that if the Fed injected enough liquidity into the financial system, we could avoid deflation. We thought if the government ran a big enough deficit, we could end a recession. It turned out we were wrong."

The root of the problem remained the US's property bubble, which continued to deflate. Many people had assumed that by the end of 2008 the worst must be over. It was not. House prices continued to slide in the US. As they did, more and more families found themselves in negative equity, with debts exceeding the value of their homes. In turn, rising foreclosures translated into bigger losses on mortgage-backed securities and yet more red ink on banks' balance sheets.

With total debt above 350 per cent of US gross domestic product, the excesses of the age of leverage proved difficult to purge. Households reined in their consumption. Banks sought to restrict new lending. The recession deepened. Unemployment rose towards 10 per cent, and then higher. The economic downward spiral seemed unstoppable. No matter how hard they saved, Americans simply could not stabilise the ratio of their debts to their disposable incomes. The paradox of thrift meant that rising savings translated into falling consumer demand, which led to rising unemployment, falling incomes and so on, ever downwards.

"Necessity will be the mother of invention," Obama declared in his inaugural address on January 20. "By investing in innovation, we can restore our faith in American creativity. We need to build new schools, not new shopping malls. We need to produce clean energy, not dirty derivatives." The rhetoric flew high. But the markets sank lower. The contagion spread inexorably from subprime to prime mortgages, to commercial real estate, to corporate bonds and back to the financial sector. By the end of June, Standard & Poor's 500 Index had sunk to 624, its lowest monthly close since January 1996.

The crux of the problem was the fundamental insolvency of the big banks, another reality that policymakers sought to repress. In 2008, the Bank of England had estimated total losses on toxic assets at about $2.8 trillion. Yet total bank writedowns by the end of 2008 were little more than $583bn, while total capital raised was just $435bn. Losses, in other words, were either being massively understated, or they had been incurred outside the banking system. Either way, the system of credit creation had broken down. The banks could not contract their balance sheets because of a host of pre-arranged credit lines, which their clients were now desperately drawing on, while their only source of new capital was the US Treasury, which had to contend with an increasingly sceptical Congress.

There was uproar when Timothy Geithner, US Treasury secretary, requested an additional $300bn to provide further equity injections for Citigroup, Bank of America and the seven other big banks, just a week after imposing an agonising "mega-merger" on the automobile industry. In Detroit, the Big Three had become just a Big One. The banks, by contrast, seemed to enjoy an infinite claim on public funds. Yet no amount of money seemed enough to persuade them to make new loans at lower rates. As one indignant Michigan lawmaker put it: "Nobody wants to face the fact that these institutions [the banks] are bust. Not only have they lost all of their capital. If we genuinely marked their assets to market, they would have lost it twice over. The Big Three were never so badly managed as these bankrupt banks."

In the first quarter, the Fed continued to do everything in its power to avert the slide into deflation. The effective federal funds rate had already hit zero by the end of 2008. In all but name, quantitative easing had begun in November 2008, with large-scale purchases of the debt and mortgage-backed securities of government-sponsored agencies (the renationalised mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) and the promise of future purchases of government bonds. Yet the expansion of the monetary base was negated by the contraction of broader monetary measures such as M2 (the measurement of money and its "close substitutes", such as savings deposits, that is a key indicator of inflation). The ailing banks were eating liquidity almost as fast as the Fed could create it. The Fed increasingly resembled a government-owned hedge fund, leveraged at more than 75 to 1, its balance sheet composed of assets everyone else wanted to be rid of.

The position of the US federal government was scarcely better. By the end of 2008, the total value of loans, investments and guarantees given by the Fed and the Treasury since the start of the crisis had already reached $7.8 trillion. In the year to November 30 2008, the total federal debt had increased by more than $1.5 trillion. Morgan Stanley estimated that the total federal deficit for the fiscal year 2009 could equal 12.5 per cent of GDP. The figure would have been even higher had Obama not been persuaded by his chief economic adviser, Lawrence Summers, to postpone his planned healthcare reform and promised spending increases in education, research and foreign aid.

Despite the fears of the still-influential former Treasury secretary Robert Rubin, investors around the world were more than happy to buy new issues of US Treasuries, no matter how voluminous. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the quadrupling of the deficit did not lead to falling bond prices and rising yields. Instead, the flight to quality and the deflationary pressures unleashed by the crisis around the world drove long-term yields downwards. They remained at close to 3 per cent all year.

Nor was there a dollar rout, as many had feared. The foreign appetite for the US currency withstood the Fed's money-printing antics, and the trade weighted exchange rate actually appreciated during 2009.

Here was the irony at the heart of the crisis. In all kinds of ways, the Great Repression had "Made in America" stamped all over it. Yet its effects were more severe in the rest of the world than in the US. And, as a consequence, the US managed to retain its "safe haven" status. The worse things got elsewhere, the more readily investors bought Treasuries and held dollars.

For the rest of the world, 2009 proved to be an annus horribilis . Japan was plunged back into the deflationary nightmare of the 1990s by yen appreciation and a collapse of consumer confidence. Things were little better in Europe. By the first quarter of 2009, it became apparent that the problems of the European banks were just as serious as those of their American counterparts. Moreover, in the absence of a European-wide finance ministry, all talk of a European stimulus package was just that - mere talk. In practice, fiscal policy became a matter of sauve qui peut , with each European country improvising its own bailout and its own stimulus package. The result was a mess.

Political instability struck China, where riots by newly redundant workers in Shenzhen and other export centres provoked a heavy-handed clampdown by the government, but also a renewed effort by the People's Bank of China to prevent the appreciation of the yuan by buying up yet more hundreds of billions of dollars of US Treasuries. "Chimerica" - the symbiotic relationship between China and America - not only survived the crisis but gained from it. Although Obama's decision to attend the first G2 summit in Beijing in April dismayed some liberals, most recognised that trade trumped Tibet at such a time of economic crisis.

This asymmetric character of the global crisis - the fact that the shocks were even bigger on the periphery than at the epicentre - had its disadvantages for the US, to be sure. Any hope that America could depreciate its way out from under its external debt burden faded as 10-year yields and the dollar held firm. Nor did American manufacturers get a second wind from reviving exports, as they would have done had the dollar sagged. The Fed's achievement was to keep inflation in positive territory - just. Those who had feared galloping inflation and the end of the dollar as a reserve currency were confounded.

On the other hand, the troubles of the rest of the world meant that in relative terms the US gained, politically as well as economically. Many commentators had warned in 2008 that the financial crisis would be the final nail in the coffin of America's credibility around the world. First, neoconservatism had been discredited in Iraq. Now the "Washington consensus" on free markets had collapsed. Yet this was to overlook two things. The first was that most other economic systems fared even worse than America's when the crisis struck: the country's fiercest critics - Russia, Venezuela - fell flattest. The second was the enormous boost to America's international reputation that followed Obama's inauguration.

If proof were needed that the US constitution still worked, here it was. If proof were needed that America had expunged its original sin of racial discrimination, here it was. And if proof were needed that Americans were pragmatists, not ideologues, here it was. It was not that Obama's New New Deal produced an economic miracle. It was more that the federal takeover of the big banks and the conversion of all private mortgage debt into new 50-year Obamabonds signalled an impressive boldness on the part of the new president.

The same was true of Obama's decision to fly to Tehran in June - a decision that did more than anything else to sour relations with Hillary Clinton, whose supporters never quite recovered from the sight of the former presidential candidate shrouded in a veil. Like Richard Nixon's visit to China in 1972, it symbolised a readiness on Obama's part to rethink the very fundamentals of American grand strategy. And the downfall of the Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad - followed soon after by the abandonment of the country's nuclear weapons programme - was a significant prize in its own right. With their economy prostrate, the pragmatists in Tehran were finally ready to make their peace with "the Great Satan" in return for desperately needed investment.

Meanwhile, al-Qaeda's bungled attempt to assassinate Obama only served to discredit radical Islamism and to reinforce Obama's public image as "The One".

By year end, it was possible for the first time to detect - rather than just to hope for - the beginning of the end of the Great Repression. The downward spiral in America's real estate market and the banking system had finally been halted by radical steps that the administration had initially hesitated to take. At the same time, the far larger economic problems in the rest of the world had given Obama a unique opportunity to reassert American leadership.

The "unipolar moment" was over, no question. But power is a relative concept, as the president pointed out in his last press conference of the year: "They warned us that America was doomed to decline. And we certainly all got poorer this year. But they forgot that if everyone else declined even further, then America would still be out in front. After all, in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king."

And, with a wink, President Barack Obama wished the world a happy new year.

Deflationary shock

First a personal disclaimer: It is not that I was so smart to get out of the market, just that I was too stupid to get in. Couldn't figure out why the McMansions offered 'captivating value', why stocks were just going to keep going up, why oil would go to $200 ... so I opted out. Took a Chauncey Gardener approach and learned a lot by watching. My belief is that Chauncey will be wearing toothpicks under his eyelids in 2009.

'The mendacity of hope and the urgency of not', should be the investors' mantra in this new Year of our Lord but unfortunately the lure of easy money doesn't fade easily - it literally has to be beaten out of a fella. Folks need to appreciate that fortunes weren't lost in 1929, they were lost by buying all the way down. Stocks bottom when no one cares.

Much has been made of looking at history to predict today's woes. B.S. Bernakke, a student of history, seems determined to make his own mistakes. The best he can do, in this humble blogger's opinion is to concentrate the timeline by truncating the misery.

Since we are too timid to drop the banks in the acid bath of price discovery as Sweden did, our alternative is too accelerate the Japanese process by flooding the insolvent banks with liquidity, removing all incentives to being risk-adverse by threatening to monetize cows, and ultimately bridging the output gap by stimulating anything that moves.

Try as we might though, the creative destruction of Mr. Market will continue, albeit in a much more temporally compressed form then the historical slideshow of our eastern friends.

As I sit on a Scrooge McDuck pile of powder, certainly I would like to be an investing smartypants too. Armed with the knowledge that the moment to deploy funds is when every emotional neuron is screaming 'oh hell no!' here is what I am looking for - with the admonition that if I am wrong I lose only opportunity.

Simply put, I am waiting for gold to crash.